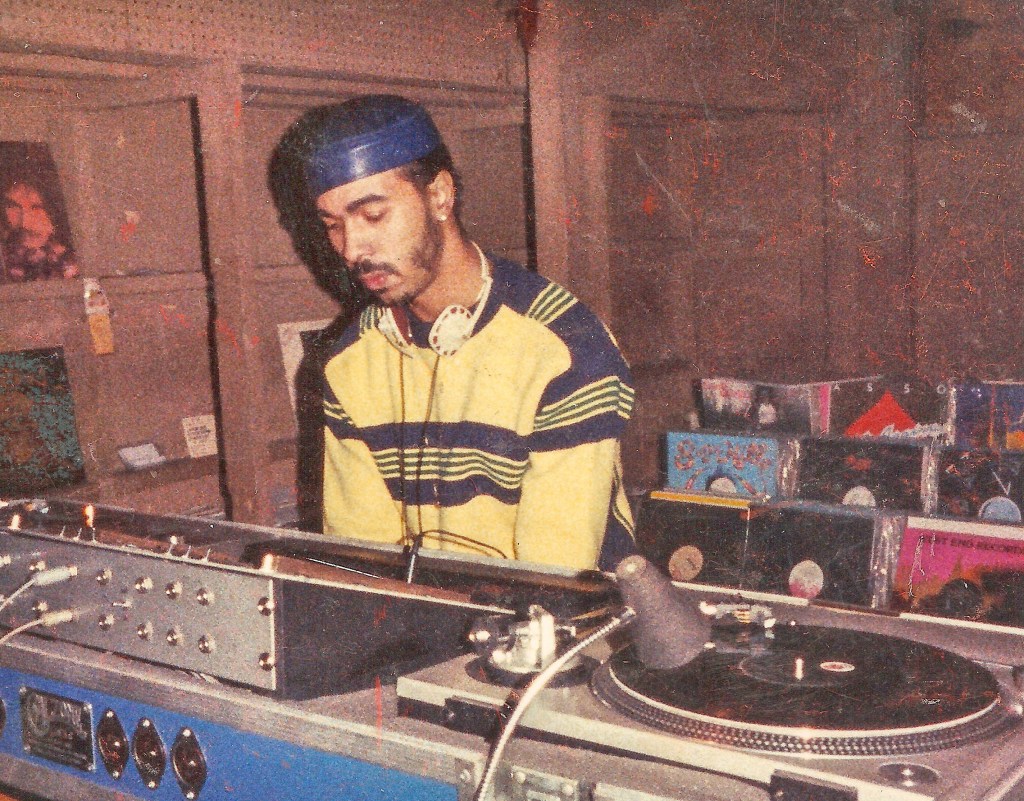

Frankie Knuckles

People love to say “not everything is political.” But life itself is political. From the air we breathe, the food we eat, and the spaces where we gather. Music has always been part of that fight, whether on a sweaty dancefloor in Chicago, a warehouse in LA, a drag performance in Puerto Rico, or a protest in Compton. The beat has always carried resistance and sometimes this resilience is shouted through a mic or sometimes whispered through the baseline.

House music emerged from the ashes of disco and the underground clubs of 1970s New York, where queer and Black communities gathered to dance through the weight of discrimination. When mainstream clubs began enforcing racist and homophobic dress codes, policing who could enter and how they could move, underground spaces became laboratories of freedom. In Chicago, DJ Frankie Knuckles, often called the “Godfather of House,” transformed the Warehouse into a sanctuary for queer and Black dancers seeking release from segregation, police surveillance, and moral panic. His extended mixes stitched gospel, soul, and disco into a new sonic language of resilience. Meanwhile, artists like Sylvester, an openly gay disco icon, made joy itself political with his 1978 anthem You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) turned the dance floor into a church for the marginalized. In New York, ballroom culture flourished as Black and Latinx queer and trans people built chosen families known as “houses,” where performance, fashion, and voguing became forms of survival and self-definition. Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning captures how these spaces carved joy from exclusion, offering a mirror ball against systemic neglect. Together, these movements bridged sound and resistance, shaping the later rave cultures of Chicago, Detroit, and Los Angeles, each beat an act of defiance against homophobia, patriarchy, transphobia, and racial profiling. House music became a refuge, a revolution, and the rhythm of a people who refused to be erased.

Paris is Burning Trailer on YouTube

The legacy of house music did not end in the 1980s. Its pulse carried west, crossing from Chicago’s warehouses into Los Angeles’s queer Latinx nightlife. By the 1990s, new generations were remixing that sound through their own struggles with race, gender, and belonging. One of the loudest voices in that transformation was DJ Irene, whose high-energy sets at Hollywood’s Arena Nightclub turned the politics of the dancefloor into a call for queer Latinx visibility. As Eddy F. Álvarez Jr. (2018) writes in “How Many Latinos Are in This Motherf**ing House?”*, Irene’s mixes created sonic interpellations of dissent and queer Latinidad in 1990s Los Angeles.

In the mid-1990s Los Angeles queer club scene, DJ Irene born Irene M. Gutiérrez emerged as a powerful sonic figure who carved out visibility for queer Latinx youth when many mainstream spaces excluded them. She held down regular sets at Arena Nightclub in Hollywood, a massive warehouse-turned-club that welcomed ravers, drag queens, Latinx teenagers, youth of color, and other marginalized crowds. Her trademark shout-out: “How many motherfucking Latinos are in this motherfucking house?” became a ritual proclamation of belonging and a moment of sonic interpellation: a call that named and affirmed a community which was otherwise made invisible.

The context was charged: L.A. in the 1990s was grappling with racial and political tensions, the 1992 Los Angeles riots, anti-immigrant Proposition 187, ongoing homophobia and HIV/AIDS impact in Latinx communities. Against this backdrop, Irene’s music functioned as an emancipatory space of queer Latinidad, enabling bodily and sonic dissent. Her invite into the “house” signified a provisional home, a community of rhythm and resistance, for brown queer youth who otherwise faced exclusion via policing, dress-codes, and race/gender discipline. (read more from Sounding Out! )

In this way, DJ Irene’s sets at Arena operated as both sonic archive and cultural practice: the stomp of feet, clap of the “Arena clap,” the mix of house music, hip-hop, and drag performance all combined to constitute queer Latinx world-making in liminal space. The dance floor became site of cultural citizenship and self-making.

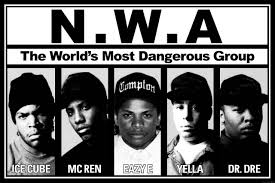

In the late 1980s, the resistance that once pulsed through disco floors found new rhythm in the streets of South Central Los Angeles and Compton. Amid police brutality, gang injunctions, and Reagan-era disinvestment, N.W.A. became the sonic megaphone for a generation living under siege. Their 1988 album Straight Outta Compton turned rage into reportage, documenting racial profiling, surveillance, and state violence long before smartphones could. Songs like “F*** tha Police” were testimonies of their experiences. The group’s members: Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, MC Ren, and DJ Yella used music to narrate daily realities the media criminalized or ignored.

The 2015 film Straight Outta Compton, directed by F. Gary Gray, visualizes this emergence of rap as political archive, showing how N.W.A.’s lyrics were shaped by constant LAPD harassment and censorship. The infamous FBI letter demanding they cease performing “F*** tha Police” only demonstrated the power of their dissent. Their sound was born from surveillance and survival.

In many ways, N.W.A. extended the lineage of sonic resistance heard in Chicago’s house and LA’s queer clubs spaces where sound spoke truth when words alone could not. Through turntables instead of drum machines, N.W.A. channeled community trauma into collective empowerment. Their beats were documentation, a refusal to be silenced. As with the dancefloor, the streets of Compton proved that the body (whether moving or marching) has always been political.

The politics of sound does not end in the streets of Compton, it shifts frequencies. Where N.W.A. fought systemic violence through lyrical confrontation, today’s artists like Bad Bunny weaponize rhythm, gender, and performance to challenge other structures of power. The microphone that once amplified resistance to police brutality now shows through global pop, reclaiming bodies policed by patriarchy and colonialism. Bad Bunny’s Yo Perreo Sola transforms the club into a stage of liberation, extending the same defiant lineage that N.W.A. began, this time through twerking, drag, and perreo.

Bad Bunny in Yo Perreo Sola

In 2020 Bad Bunny released Yo Perreo Sola, a track and video that push reggaetón’s dancefloor into the terrain of gender, autonomy, and queered embodiment. The main message of this music video is displayed in Spanish: “Si no quiere bailar contigo, respeta; ella perrea sola” (“If she doesn’t want to dance with you, respect it; she dances alone”). This then transforms perreo which is traditionally danced with partners in reggaetón clubs into a declaration of self-possession and refusal.

According to the Bad Bunny Syllabus, this work must be situated within larger frames: Puerto Rico’s colonial history, shifts in Latinx masculinities, queering of the urbano soundscape, and reggaetón’s long struggle with misogyny and hyper-masculinity. By taking the voice of a woman (“yo perreo sola”) and translating it through his body, Bad Bunny enacts sonic interpellation: he invites both women and queer listeners into a space free from male gaze and patriarchal obedience. The drag transformation is a political one that reinscribes the club floor as a site of dissent, where those historically excluded (women, trans and queer bodies) can inhabit sound, movement, and visibility on their own terms.

In this way, Yo Perreo Sola signifies a lineage of dancefloor activism: from queer house floors in Chicago, to Latinx ravers in LA, to now a global pop star whose very body flips the script of who can have the mic, the beat, and the floor.

also watch: https://youtu.be/FC43hRy6oaU?si=BmHjrlMN64rfPyhN: Everything Is Political Including the Dancefloor https://youtu.be/nI7EhpY2yaA?si=j2keSGvS2uN0nnSB: Everything Is Political Including the Dancefloor

Leave a comment