Coming to Miami for the second time this year for Art Basel 2025 rejuvenates my spirit. I feel more alive there, held by a kind of “main character” energy that I do not always feel in Southern California. Traveling during week ten of the quarter and the beginning of finals made something click for me: my ability to move between academic worlds and nightlife worlds as a practice. For example, Miami is where my research becomes lived knowledge. On the dancefloor, I experience pleasure through music, heat, movement, and proximity to Black and Latinx diasporic communities where identities collide, overlap, and remix. This is where I begin to think about what I call sonic geography: how sound, bodies, and space work together to produce meaning, belonging, and memory.

To make sense of why Miami feels this way to me, on why music, movement, and place feel inseparable, I turn to scholars of racial geography who help name how space is lived, unevenly structured, and felt in the body. Geographer Laura Pulido was one of the first scholars who taught me to understand space as racialized. Her work shows how racism is embedded in land use, environmental policy, and spatial organization that shapes who has access to safety, pleasure, and mobility, and who does not. Building from this structural understanding, Genevieve Carpio’s work on racial geographies in Southern California helped me see how place is also produced through culture, migration, and everyday movement. Carpio shows how racialized communities actively make meaning in and through space, even as they navigate histories of displacement and exclusion. Katherine McKittrick pushes this conversation further by insisting that Black geographies are lived, embodied, and often illegible to dominant ways of mapping space. In Demonic Grounds, she reminds me that Black spatial knowledge emerges through movement, memory, and feeling through ways of knowing that are sensed rather than officially recorded.

Taken together, these scholars allow me to think about Miami as a sensory and embodied geography, one produced through sound, mobility, heat, and diasporic encounter. This is where I begin to think through sonic geography. I define sonic geography as an embodied way of knowing place through sound, climate, and the body. In Miami, this includes the heat that sticks to your skin, the humidity that frizzes hair mid-dance, and the sweat that turns movement into labor and pleasure at once. It lives in the dehydration and dry mouth that come from drinking and dancing for hours, in the smell of bodies pressed together, and in the way bass moves through chests rather than ears alone. Sonic geography in Miami also holds the Latin samples woven into remixed tracks: sonic traces of diaspora that collapse language, memory, and migration onto the dancefloor. Together, these sensations produce a geography that is mapped beyond streets or borders. It is a feeling, movement, and collective presence.

On my first day in Miami, I head to Wynwood, where I am staying for the entire Art Basel experience. The neighborhood feels alive and layered in murals, different Spanish accents, different foods bleeding into one another. I find myself craving aguachiles, something cold and grounding in the heat, so I decide to go to Bakan during happy hour.

Immediately, Bakan feels intentional. There are plants everywhere that wrap around the outdoor seating and spilling into the interior that blurs the line between inside and outside in a way that mirrors Miami’s humidity. It is known for its mezcal bar, my ultimate favorite drink, and during happy hour almost everything is half off. Mezcal feels right in this moment: smoky, earthy, slow, a drink meant to be sipped while sweat settles on your skin.

Aguachiles and Drinks from Bakan

We end up talking with our waiter, who quickly becomes a friend. He tells us he is Honduran and immediately recognizes our Mexican Spanish accent, something that feels both intimate and grounding. He mentions he lived in Los Angeles for a year, but that he loves Miami for its Latinx diversity, a place where different accents, histories, and migrations that coexist with each other.

While we are eating, the manager comes over and unexpectedly brings us a free round of drinks, insisting that we stay longer. He tells us they have a DJ on Tuesdays and Fridays starting at 8 p.m., as if the night is only just beginning. The invitation feels easy and generous, not transactional which I saw as an extension of the space itself, where music, language, and hospitality move together.

Before stepping into a club, this was already Miami teaching me how sound, accent, and movement create belonging.

After dinner, I meet up with friends from Southern California and we head back to get ready for Club Space, for the Black Book Records takeover and, most importantly, my bestie Marco Strous’s Space debut. It is his first time playing there, a milestone that feels collective, something we are all stepping into together.

Club Space is legendary for a reason. It is one of the few places where time feels suspended, where partying stretches past sunrise because Miami’s 24-hour alcohol licensing allows the night to dissolve into morning. The club regularly hosts international house and techno DJs that turns the dancefloor into a crossroads of global sound and local devotion. And yet, what makes Space feel human are the small rituals: grilled cheese sandwiches for when hunger hits at 8 a.m., espresso martinis and mimosas circulating alongside sweat-soaked bodies, caffeine and alcohol blurring the line between night and day.

At Space, endurance becomes part of the experience. Dancing here is about staying, listening, moving, refueling, and moving again. Just like a marathon. This is where Miami’s sonic geography fully reveals itself: in the refusal of closure, in the insistence that pleasure does not need to end just because the sun comes up.

Chris Lake, Chris Lorenzo, but most meaningfully, witnessed my bestie Marco Strous make his Club Space debut. Watching him play there filled me with pride. I remember when he had barely 5,000 followers on Instagram, grinding quietly, perfecting his craft. Now, his growth is visible through the recognition he is receiving for his sharp samples and meticulously layered mixes. Seeing him take up space at Space felt like a full-circle moment, a reminder that talent and persistence eventually find their audience. He is known for sampling 69 Boyz who are a popular 1994 Miami hip-hop group from Jacksonville, Florida.

Another night I hold close is Paradise, curated by Jamie Jones. I bought a before-3 a.m. ticket and committed myself to pacing through the night into the next day, waiting until 4 p.m. to finally see Alisha play, a rare moment, since she barely comes to the U.S. That day became an exercise in care and endurance: drinking espresso, eating when I could, limiting alcohol so I would not burn out before her set. Paradise felt like an oasis, disco balls reflecting light across the crowd, plants woven into the space, decorations evoking an ’80s retro-futuristic dream. The music moved between deep basslines and Latin-inflected rhythms.

A few tracks that I remember from this event are Joshwa’s unreleased track that goes something within the lines of “I think I’m going Insane (Twisting My Beat)“, Reverse Skydiving by Hot Natured and Annabel, and Toman’s track Verano en NY that samples the iconic salsa classic “Un Verano en Nueva York” by El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico.

My favorite sets from Paradise included Jamie Jones, his back-to-back set with Joseph Capriati, Sosa, and finally Alisha b2b Max and Luke Dean. These sets made every moment worth waiting for.

However, these nights at Club Space made clear that Miami’s sonic geography is not confined to the dancefloor. The endurance, the bass, the Latin and hip-hop samples folded into house music and the way bodies move through time all highlight longer histories of migration, survival, and pleasure in the city. Wanting to ground that feeling beyond nightlife, I spent the next day at HistoryMiami Museum, tracing how Miami’s sound, rhythm, and resistance have always been shaped by movement, of people, of music, of goods, and of ideas.

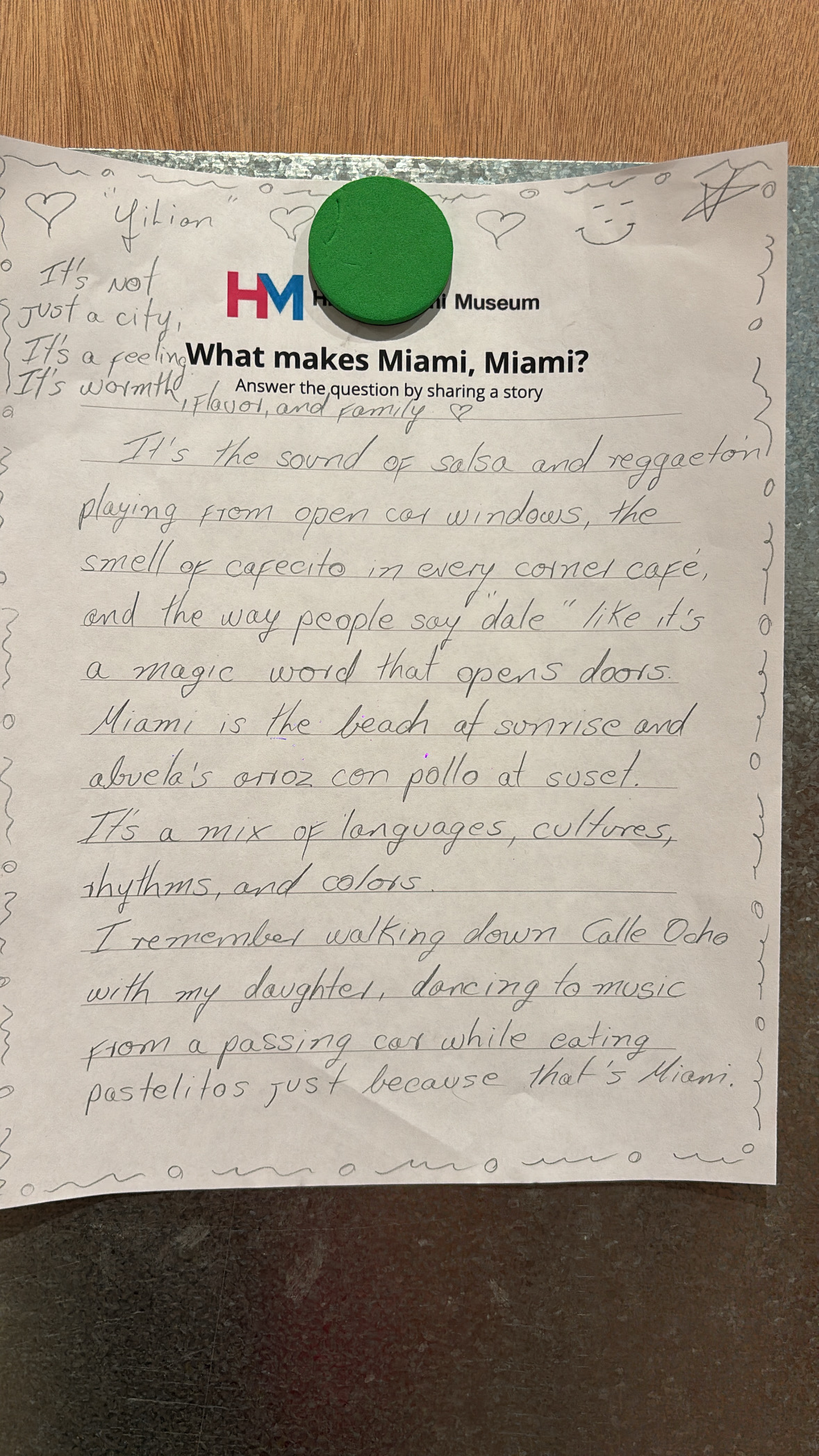

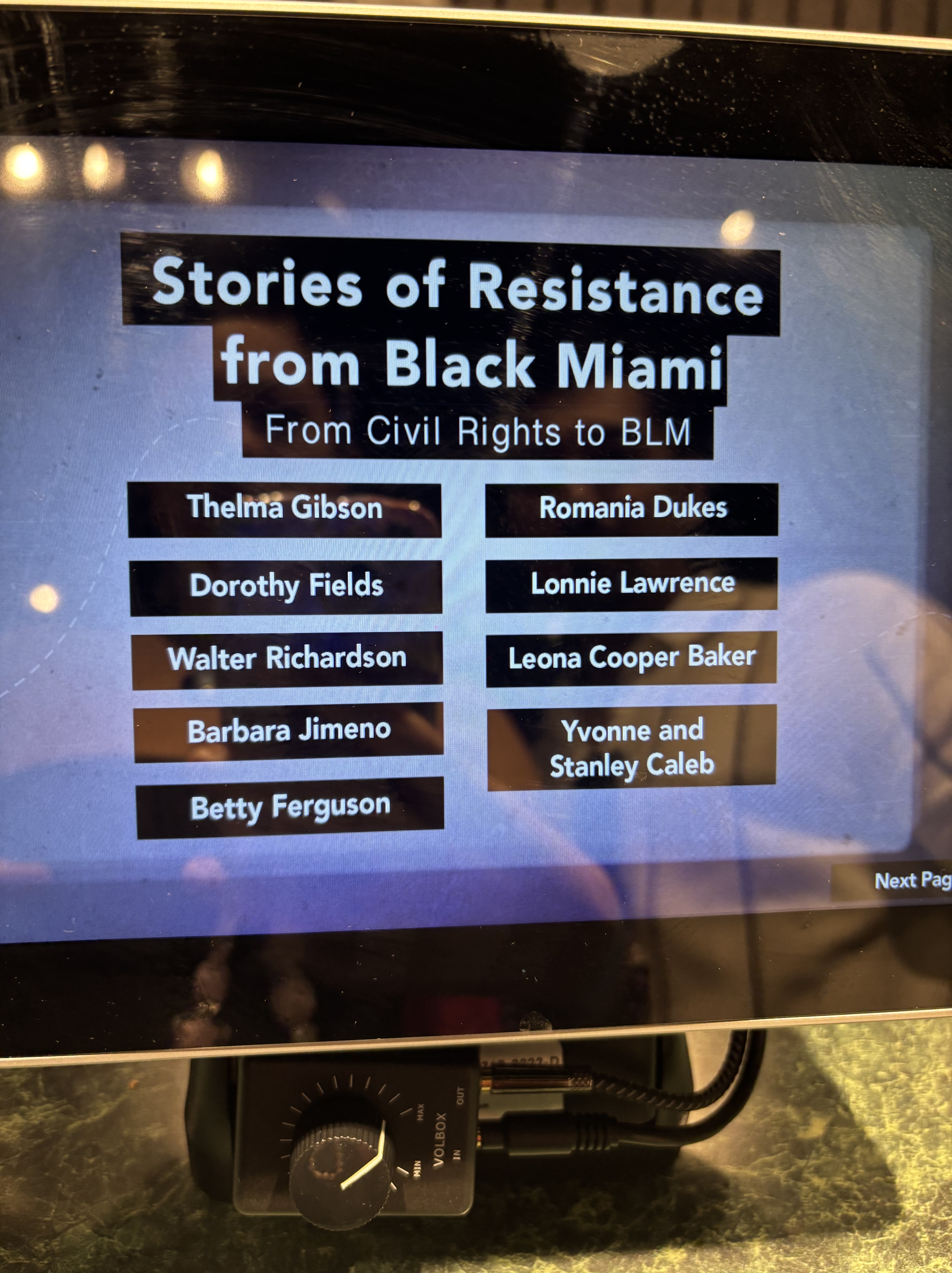

Walking through the exhibits, I learned about South Florida during Prohibition as a key site for rum runners and bootleggers, where alcohol flowed through informal networks long before Miami became known for its 24-hour nightlife. Stories of Black Miami that dated from the Civil Rights to Black Lives Matter sat alongside reflections on migration, labor, and cultural expression. What struck me most was how these histories mirrored what I had felt the night before: sound as a connector, movement as survival, and pleasure as something deeply political.

In many ways, the museum clarified what the dancefloor had already taught me. Miami’s sonic geography stretches across time from bootlegging routes and protest chants to salsa playing from open car windows and basslines rattling rooftops at sunrise. Rather than narrate this section myself, I want to let the images hold that history, memory, and resonance.

Leaving the museum, I could not help but think about how these histories mirror the dancefloor. Being in a PhD program, I am often reminded that not everyone takes my research seriously. Nightlife, dance, and partying are still too easily dismissed as unserious, especially when compared to archives that sit neatly in boxes or libraries. But cultural production has always mattered, particularly for Black, Latinx, queer, and trans communities who have historically created worlds of survival, intimacy, and possibility through music and movement. House music emerged as a refuge, a technology of care, and a space of collective becoming.

Today, those same spaces are frequently co-opted by upper-class white audiences, stripped of their histories, and repackaged as lifestyle or spectacle. And yet, there is something powerful about continuing to take up space where we are told we do not belong, about insisting that joy, pleasure, and rest are not distractions from struggle, but part of how people endure it. To experience joy amid chaos, to dance on land shaped by violence, displacement, and extraction is very much intentional. In Miami, joy felt earned, practiced, and shared. Sonic geography helps me name that feeling: pleasure not as escape, but as knowledge, as memory, as refusal to disappear

Leave a comment